On the road back from Fatehpur Sikri to Agra, you will probably grasp the meaning of those strange conical piles, about twenty feet high, lining the road. They are kos minars, milestones placed on the road by the Moghuls.

But now, Agra is only a crossroad stop on your trip south. Seventy two miles away by car or train, you reach Gwalior and a new chapter in Indian history. Here, the Moghuls played only a minor walk-on role near the end of a long drama.

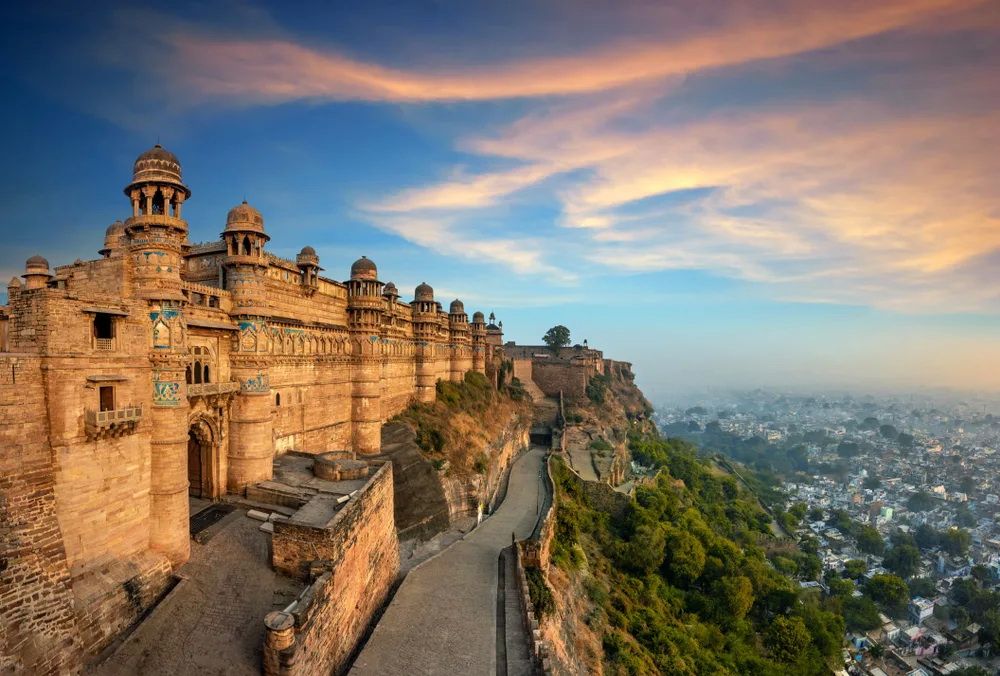

Gwalior is practically synonymous with its Fort, one of the oldest in India (it is mentioned in an inscription dated 525 A.D.). The story of its founding is told in the pleasant legend of Suraj Sena, a local leader suffering with leprosy, who met a Hindu saint, Gwalipa, on the rocky hill where the fort now stands. Gwalipa offer him water from a blessed pool and the leper was cured. Gwalipa then directed him to build a fort on the spot (the derivation of the name Gwalior) and to use the name of Pal if wanted his dynasty to survive. So Suraj Pal’s family flourished until one cynic refused to obey the tradition and, naturally, was deposed.

The grandeur of Gwalior dates back to another dynasty, the Tomars, who established their rule in the 14th century. It was a Tomar King, Man Singh (1486-1516) who built the Man Mandir, a six-towered palace which forms the eastern wall of the fort and one of the sights of India. Three hundred feet long and eighty feet deep, it is decorated with perforated screens, mosaics, floral designs and moldings in Hindu profusion. Beneath it, two underground floors were burrowed into the 300-foot-high hill of the fort, serving as air-conditioned summer quarters for Man Singh-and dungeons for the prisoners of the Moghuls who later took the fort under Akbar from Man Singh’s grandson.

Captured by the Marathas in 1784, the Gwalior Fort was the scene of fierce fighting again in 1857 when it served as the base for 18,000 Indians who rose against the British in the Sepoy Revolt, the beginning of India’s struggle for independence. They made their last stand here under Tantia Tope and a woman hero, Rani Lakshmi Bai of Jhansi. The Rani’s cenotaph can be seen in Gwalior.

Man Singh also built the Gujari Mahal, a turreted palace of stone-now the home of an archaeological museum deserving a visit-and he built it for love. The king met a Gujar maiden, Mriganayana (the “Fawn-Eyed”), famed for her feats as a slayer of wild animals. She agreed to marry him only if he brought the waters of the Rai River, the secret source of her strength, into the fort. So, for the sake of his bride, Man Singh built the Gujari Mahal and an aqueduct linking it to the Rai.

Visiting the Gwalior Fort is something in the nature of a pilgrimage, if only because of the toilsome climb leading up to its gates ( a road once used by elephants bearing royalty, it is too steep for cars ). Fittingly enough, the fort contains a mosque on the site of the shrine of Saint Gwalipa; Chaturbhui Mandir temple housing a four-armed idol of Vishnu; and five groups of gigantic Jain sculpture carved out of rock walls. The biggest, the image of the first Jain pontiff, Adinath, is 57 feet high with a foot measuring nine feet. It was executed in 1440.

Vishnu also reigns in 11th century temples known as Sas Bahu (the mother-in-law and daughter-in-law temples). Another temple, the Teli-ka-Mandir, is the highest building in the fort with its 100-foot tower. It’s an interesting blend of Dravidian architecture from south India, typified by this spire, with Indo-Aryan decoration on its walls. Finally, there is the Suraj Kund, perhaps the oldest Gwalior shrine for it is the pond from which Suraj Sena drank.

Outside the fort, Gwalior offers the tomb of Muhammad Ghaus, a Moslem saint worshipped by the Moghuls, and the tomb of Tansen, one of Akbar’s court musicians, which is still venerated by musicians. Lashkar, a mile from the fort, is a “modern” city built in 1809 on the site of an encampment. Worth seeing there are two palaces, the Jai Vilas and the Moti Mahal, and picturesque bazaar, the Jayaji Chauk.