While most visitors to Italy are aware of the history of the destruction of Pompeii, and many have visited its famous ruins, relatively few people know of the other Napolitan city that was also destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius on August 24th, 79 A.D.

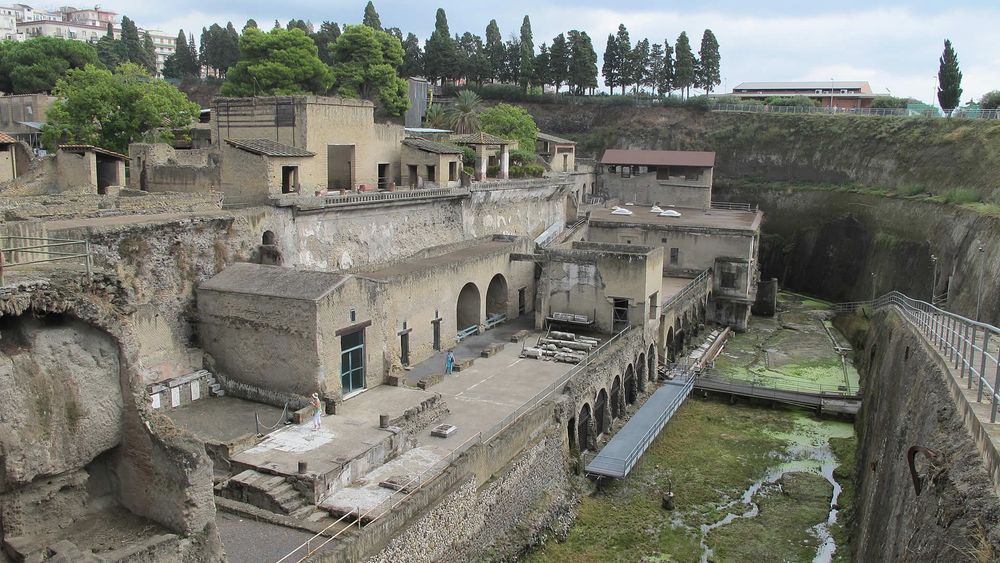

On that fateful day, the skies above the prosperous city of Herculaneum grew dark as ash, pumice and thick mud rained down from the top of nearby Mount Vesuvius, in what would become one of the most famous volcanic eruptions in history. In a remarkable state of preservation across the centuries, Herculaneum’s fascinating remains are well worth visiting.

On the day of its destruction, Herculaneum was upwind from the Mount Vesuvius volcano, so whereas Pompeii, being downwind, was buried quickly under a blanket of ash, Herculaneum was devastated almost half a day later when the blast cloud collapsed in on itself, sending forth from its spout a deadly pyroclastic flow (an avalanche of volcanic gas, pumice, hot ash and rocks).

This burning avalanche sped from the mountaintop at speeds of over 60 mph and burned at over 760 degrees Fahrenheit. Reaching the city in approximately 5 minutes, the flow destroyed everything in its path. Within 12 hours, the entire city was buried under 65 feet of ash and rubble. Though Pompeii claims much more popular recognition, Herculaneum’s buildings and streets are in a state of much greater preservation due to the effects of the pyroclastic flow, which carbonized a good portion of the wood used in the construction of many of the shops and houses.

Herculaneum was first discovered in the early 18th century as a foundation was being dug for the building of a well. When the magnitude of the find became apparent closer to the end of the century, the site began to be more seriously excavated. However, not only did the cities of Resina and Portina arise in this area during these years, but the early tunnels and portables dug up for exploration were insufficient for major excavations and eventually completely collapsed. Much of the city of Herculaneum remains hidden underground to this very day.

The City

In its heyday, Herculaneum was a peaceful and affluent Roman villa town. The city’s streets were tightly packed with houses and shops. Its main street was closed off to wagons and carts to allow pedestrians to wander around at their leisure, and many of the sidewalks were covered with awnings to shelter shoppers from bad weather. Herculaneum also had an extremely efficient and sanitary plumbing system. Aquaducts directed fresh water from the mountains to be filtered and stored in the public water tower. From there, the water was dispensed to the city’s shops, water-fountains, baths and even to private homes.

Such a complex water system was imperative in any affluent Roman city in order to properly operate the luxurious and sprawling public baths, which themselves were one of the most important social sites in ancient Rome. Oftentimes, the wealth of a Roman town was measured and displayed by the opulence of its public baths.Bright mosaics and both painted and carved frescoes adorned the walls of the baths, whose marble sinks and fountains, beautifully tiled floors and decorative statues added to the luxury and splendor of these important Roman social sites. Roman baths were open to the entire public, both men and women, and were normally visited at least once a day. A typical trip to the baths would include a workout in the neighboring gymnasium (for men), followed by a rub down by an attending slave (this consisted of being slathered with olive oil and pumice to coat the body, then being scraped clean with a strigil to get rid of excess dirt and sweat). A visit to the tepidarium (the warm room), would come next, followed by a stop in the caldarium (hot room) topped off with a visit to the chilly frigidarium (cold room).Among other favored Roman social activities were sporting events, a fact attested to by the huge arena found in Herculaneum, which spans almost an entire city block. The main hall of the arena, called the Palaestra, housed within it a large statue of the namesake of the city – the infamous Greek hero, Hercules.

Getting There

There are many touring coaches and other modes of transportation that will quickly take visitors to the site from the nearby city of Naples. One can also take the Circumvesuvia train, which arrives and departs at the Ercolano Scravi station. It is a good idea to pick up a guidebook before touring the site, or to travel along with a tour group. Keep in mind that it can get quite hot in the high summer, with little shade along many of the streets, so if you are traveling in the high season, wear comfortable shoes and bring lots of water!